The other Prioress's Tale

)

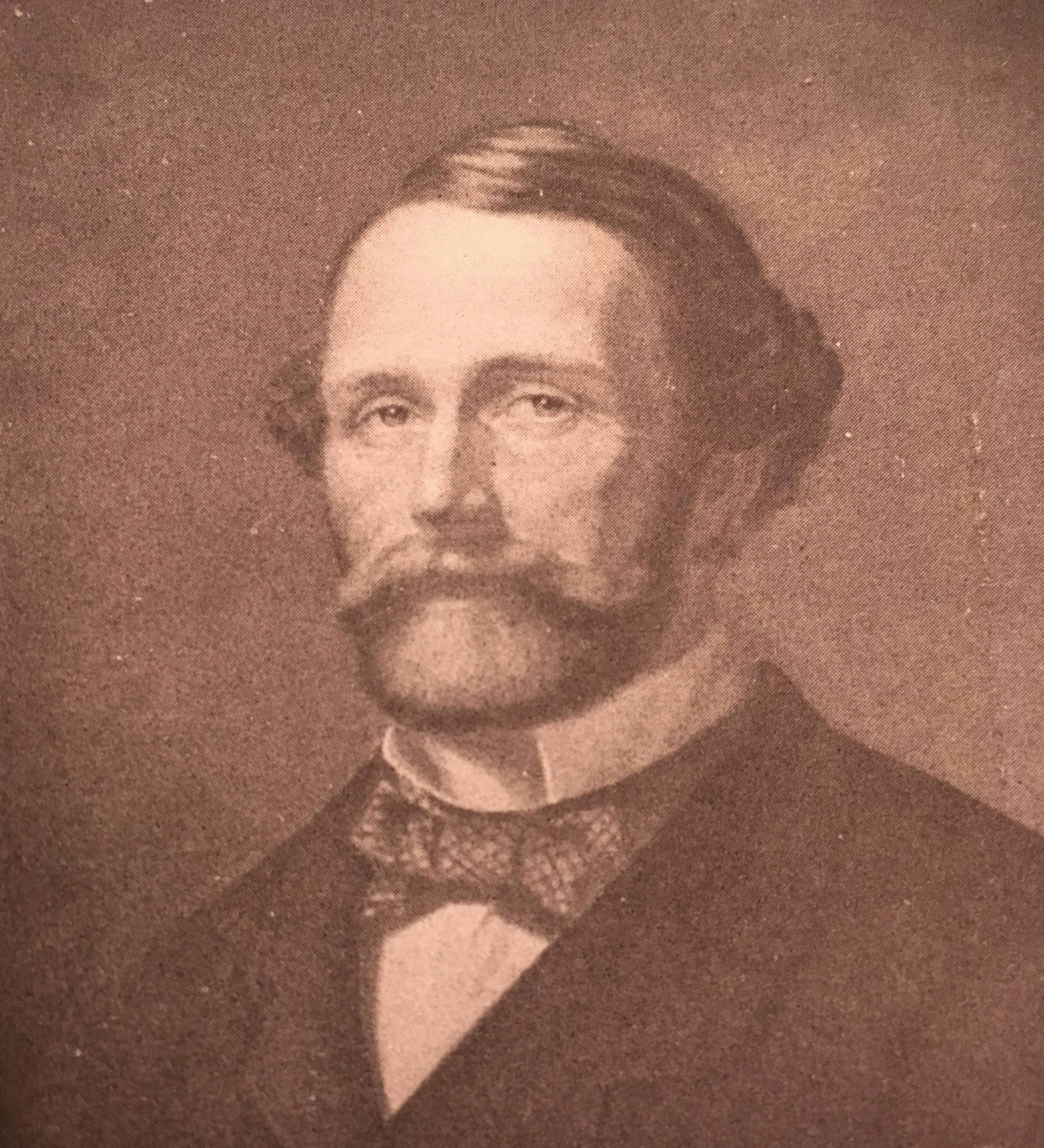

Richard Ten Broeck campaigned Prioress, the first American Thoroughbred to win a race in England (National Museum of Racing image via William H.P. Robertson's History of Thoroughbred Racing in America)

by TERESA GENARO

“My lady prioress, and by your leave,

So that I knew I should in no way grieve,

I would opine that tell a tale you should,

The one that follows next if you but would.

Now will you please vouchsafe it, lady dear?”

“Gladly,” said she, and spoke as you shall hear. (Chaucer’s The Prioress’s Tale)

Back in 2008, a former iteration of the history of the Prioress Stakes on the NYRA website offered the following:

The PRIORESS was named for the first American Thoroughbred ever to win in England. Prioress was bought by Ten Braek (sic) from General Wells as a three year old in 1857 for $2,500. She was then sent to England where she won both the Great Yorkshire Stakes and the Cesare Witch (sic) Handicap in 1858. In the latter, Prioress finished in a triple dead heat with El Hakim and Queen Bess; she then won the run off.

This English teacher was intrigued, not least of all because of the Chaucer connection, but also because the coverage of the Cesarewitch, which sounds like a pretty remarkable race, was spotty in the English archives I could access. The Times of London provided coverage of the betting and odds in the weeks prior to the race, but to my surprise, I uncovered nothing in that publication about the race itself. Fortunately, stateside turf writers provided a wealth of information.

In 1922, the Daily Racing Form offered a history of the race; initiated in 1839 at Newmarket, the Cesarewitch was funded by Russia’s Grand Duke Alexander, who became Czar Alexander II. He gave 300 pounds to endow the race, and it was named in his honor, an Anglicization of Tsarevich, the term for the heir to the title of Tsar. And beginning in the summer of 1857, when Prioress and her stablemate Pryor were sent to race in England, the New York Times ran segments from both reporters and readers as the weights for their races were assigned, provoking much discussion.

The Times printed articles and responses from Americans and Brits alike, appalled by the high weights assigned to the American horses and accusing the Brits of being unsportsmanlike. The two horses finished poorly in the Goodwood Cup, and as a result, Prioress was assigned lighter weight when she ran in the Cesarewitch. The race was reported as one of a series of items in an article entitled “Important From Europe.” Prioress went off at 100 – 1 in the race run at two miles, two furlongs, and 28 yards (remarkable precision, that), and we are told of the finish:

One of the most exciting Cesarewitch finishes ever seen then ensued. Prioress half way up the cords seemed to be about coming in alone, but the tiny jockeys of El Hakim and Queen Bess made a determined set to, and the judge unable to separate the first three pronounced a dead heat…

If the horses couldn’t be separated after that distance, how, then, to determine a winner? Why, run it again! Of course! But wait…there’s more…

It appears that after the dead heat Prioress was given a gallop of three miles to limber her up, but it did not seem to hurt her. Over seven miles galloping, and some of it at racing pace, was quite sufficient for one day. (DRF, February 1917)

Lightweights.

Prioress was the second choice in the three-horse deciding heat, and she won by a length and a half. The Times tells us that “a loud and prolonged cheer hailed the American colors, and Mr. Ten Broeck was warmly congratulated upon the first victory achieved by him in England.”

Mr. Ten Broeck, who had laid out a considerable amount of money for his racing ventures, especially his heretofore unsuccessful English foray, no doubt let out a loud and prolonged cheer himself, as he is said to have been “a great bettor” who put wagers on his mare at odds of 100- or 150-1, the bookmakers thinking it “finding money to lay against the American mare.” Credit for the victory was given to American training methods, in which horses were accustomed to running in long-distance heats.

Alas, not everyone looked so favorably upon Prioress’s historic victory, and the New York Times published two terrifically smug letters from a reader in Newmarket. The Cambridgeshire Handicap to which the writer refers takes place within weeks of the Cesarewitch, and the races are known as the Autumn Double.

The first letter was written following Prioress’s victory in the Cesarewitch but prior (pun not intended but acknowledged) to the running of the Cambridgeshire Handicap, and our writer doesn’t hide his disdain for the American Thoroughbred:

The very childish elation evinced by most of the papers in regard to this race, and particularly by one of this City that pretends to a profound knowledge of the merits of English racers and racers, is, to say the least, perfectly ridiculous. Any one who can claim for Prioress a victory over all England by the result of the race for the Cesarewitch, must certainly be ignorant of racing, or be possessed of an unaccountable share of impudence…

Following a detailed discussion of the horses Prioress beat and the weights they carried, the author concludes,

After reviewing the matter fairly, I think all racing men will agree with me that Prioress is only a very second-rate animal, though possessing good lasting qualities, which, when very favorably weighted, (she was certainly was in the above race, as well as the Goodwood Cup,) will enable her to fall through occasionally.

He finishes his letter by predicting that Prioress will finish no better than fourth in the upcoming Cambridgeshire. The letter was published on November 6, 1857, and unfortunately proved right, as Prioress finished last in the Cambridgeshire, prompting our writer (who beautifully presages the advent of the on-line commenter a century and a half later, in both tone and content) to follow up.

Sir: I am curious to learn how that portion of the American Press which so confidently anticipated that the Cambridgeshire Handicap would be carried off by one of Mr. TEN BROECK’s horses will account for their signal defeat in that race.

…

The result of the Cambridgeshire Handicap must, I think, convince every unprejudiced mind that the view I took of the racing qualities of Prioress, namely, that she is only a very indifferent mare, and could have no chance with a good English horse, at fair racing weights, was the correct one [here, he is referring to his assertion in his earlier letter that Prioress carried unfairly low weight in the Cesarewitch].

While going on to offer some sporting insight into Prioress’s abilities and how they were suited to the two courses on which the Autumn Double was run, he can’t resist a final parry:

When America can produce a nag to beat the first-class English horses in a weight for age race, I for one (and I think I can answer for the English press and people too) shall hail their success with as great pleasure as would any native American. As the racing season in England is now pretty well closed, I shall bid you adieu till the commencement of the next campaign, when, with your permission, I shall occasionally trouble you with my thoughts on forthcoming events; and by that time I hope a fresh influx of American horses will be there to contend with English blood and bone.

How happy the Times editors must have been to know that they could count on being “occasionally troubled” by our writer’s insights on “forthcoming events”…and one wonders how he reacted to Prioress’s dead heat for second in the Cesarewitch a year after she won it.

Sifting through various articles about Prioress, I came across more interesting tidbits of information about mid-19th century racing than I can reasonably include here (including that Prioress was also owned by Francis Morris, the man who received the stallion *Eclipse and the mare Barbarity from Ten Broeck and went on to breed the Barbarous Battalion, members of which won the Alabama and the Travers). What didn’t emerge is the reason that Prioress has a graded stakes race named after her. Her racing career is interesting but undistinguished, and while she is the holder of an obscure and somewhat esoteric distinction—being the first American Thoroughbred to win a race in England—I’m not sure that that puts her on the same ground as horses like Ruffian, Go for Wand, and Personal Ensign, others fillies and mares with eponymous graded stakes races. Even the list of winners of the Prioress doesn’t include a lot of fillies whom we would consider especially significant to the sport.

For a filly who didn’t do much of note on the racetrack, Prioress certainly occasioned a lot of conversation and excited some strong feelings. Not perhaps, as much, as her Chaucerian namesake, but as that tale comes to an end, so too does this, and “Heere is ended the Prioresses Tale.”

Authors

Categories

FEATURED PRODUCTS

Daily Selections

Full racecard analysis/expert picks for major tracks from America's top handicappers.

Buy Nowe-ponies Picks

E-Ponies computer-based figures have been around since 1997. Using an algorithm written by the business owner and handicapper, Liam Durbin, and powered by BRIS data files, E-Ponies offers a unique, fact-based, dispassionate analysis of every horse in every race, assigning scores for speed, class, form, connections, and more. Forget which jockey owes you money! What does the data say!

Buy NowBruno With the Works

Bruno De Julio & team bring 30+ yrs experience observing racehorses to Brisnet with valuable insight into their morning routines & chances for success in the afternoons.

Buy NowValue Plays AI by Predicteform

Full race card program with easy-to-use win chances and contender classifications for every runner plus analysis of the Best Bet, Live Longshot, and Wagering Suggestions for every race.

Buy NowADVERTISEMENT