Forgotten Turf: The story of Minnesota's first Thoroughbred racetrack

)

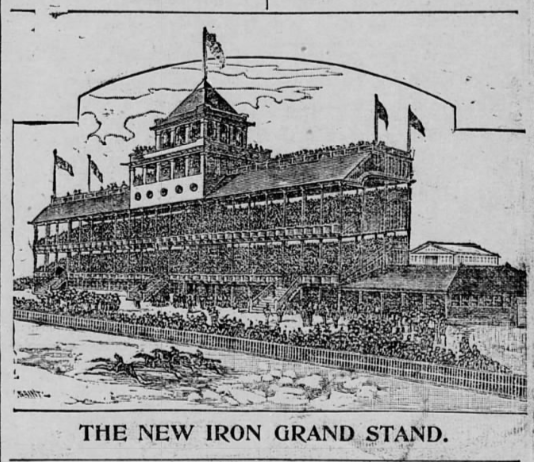

Hamline New Iron Grandstand (The St Paul Globe)

In only its second year of operation in 1986, Canterbury Downs in Minnesota nearly hit a jackpot.

The signature event of the meet was the $300,000 Saint Paul Derby in late June, and for a short time it appeared likely that Preakness (G1) winner Snow Chief, enticed by an additional $100,000 bonus for previous Grade 1 winners, would be among its participants. It would have been a significant coup for the fledgling track's growing reputation to attract a Triple Crown race winner, who also happened to be the nation's top three-year-old colt, to Minnesota of all places.

In the event, a disagreement between Snow Chief's owner and trainer regarding the colt's summer schedule, plus the application of a little muscle from Hollywood Park president Marge Everett, kept the dark brown colt home in Southern California for his next start.

While a disappointing turn of events, the Saint Paul Derby weathered Snow Chief's absence. It was awarded Grade 2 status within a couple years and stayed at that level through its final running in 1991.

Canterbury struggled financially the rest of the decade, but not before showcasing (before they were stars) 1986 sprint champion Smile, 1987 Breeders' Cup Juvenile (G1) winner Success Express, Hall of Fame mare Bayakoa, and locally-owned 1990 Kentucky Derby (G1) winner Unbridled, among others.

Little known at the time or since is that the loss of Snow Chief was not the first strike at attracting one of the nation's top three-year-olds to race in Minnesota. Indeed, it seems very little has ever been written about the state's first dalliance with Thoroughbred racing nearly a century before. It's a parochial subject, for sure, but for racing-loving natives of the state it's a rather eye-opening topic.

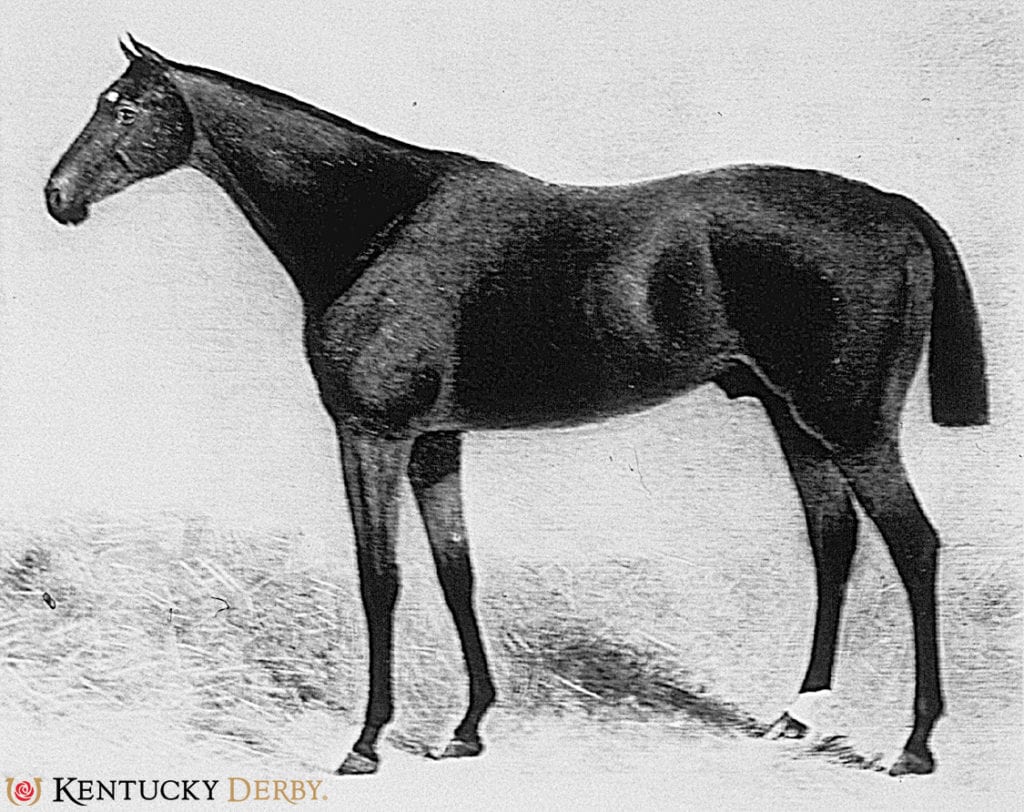

Unbridled wins the 1990 Kentucky Derby<br />(Courtesy of the Kentucky Derby/Churchill Downs)

- 1887: Thoroughbred Racing in the Midwest?

Three decades after it joined the Union, Minnesota like much of the "West" (as the Midwest was colloquially referred to) had long since embraced Standardbred racing, trotting and pacing being a primary entertainment of county and state fairs throughout the region. Following the opening of the new state fairgrounds at St. Paul (now in the incorporated city of Falcon Heights) in 1885, talk of bringing Thoroughbred racing to a metropolitan area that had grown to more than half a million souls began.

"The Northwest has always been partial to the trotting horse, principally because the trotter was first here," the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune editorialized in 1889. "The runner is a production of thickly populated sections where wealth presents every opportunity for its breeding. The Northwest is comparatively a new country, but the time for the introduction of the running horse...has fully arrived...".

Incorporated in 1887 by leading figures of local industry, some of whom who had already dabbled in Standardbred breeding and racing, the Twin City Jockey Club soon joined the American Turf Congress, an organization comprised of various racing clubs located in the "West" and South. Somewhat of a precursor to modern entities like The Jockey Club and the Thoroughbred Racing Association, the American Turf Congress took upon itself the duty of allotting racing dates to its member clubs. The inaugural Twin City Jockey Club meeting was awarded eight dates from July 23-31, 1889.

Incorporated in 1887 by leading figures of local industry, some of whom who had already dabbled in Standardbred breeding and racing, the Twin City Jockey Club soon joined the American Turf Congress, an organization comprised of various racing clubs located in the "West" and South. Somewhat of a precursor to modern entities like The Jockey Club and the Thoroughbred Racing Association, the American Turf Congress took upon itself the duty of allotting racing dates to its member clubs. The inaugural Twin City Jockey Club meeting was awarded eight dates from July 23-31, 1889.

The man in charge of promoting and putting the racing program together was club secretary (Col.) Frank N. Shaw. The Live Stock Record (later the Thoroughbred Record) would note that "...Shaw has the reputation of being one of the biggest gamblers on the Western turf, and, according to newspaper reports, one of the most successful..."

Shaw had at times run afoul of the law. In 1887 he had been indicted with operating an illegal poolroom, or book, in the Twin Cities. The charge was dismissed the following summer, with the judge ruling that:

"The risking of money between two or more persons on a contest of chance of any kind, where one must be the loser and the other the gainer, is not gambling. For such purposes a horse-race is a game, and betting thereon is not punishable under Section 206. The boards and lists described in the indictment, and alleged to be kept and used by the defendants, and the description of horse-races, and the times and places of such races, are not gambling devices within the intent and meaning of the law."This is a test case, and poolrooms may now be opened all over the State of Minnesota."

Shaw's travels to the racing centers of Kentucky, St. Louis, Chicago, and elsewhere in an attempt to drum up interest for the new track were frequent gossip items in local papers over the next several years. Chicago, at the time a 14-hour train ride from St. Paul, would provide the bulk of the stock, and the inaugural meet's dates were conveniently scheduled after the conclusion of the lucrative Washington Park meet in that city.

- 1889: "...nothing but death will prevent the Montana wonder from running..."

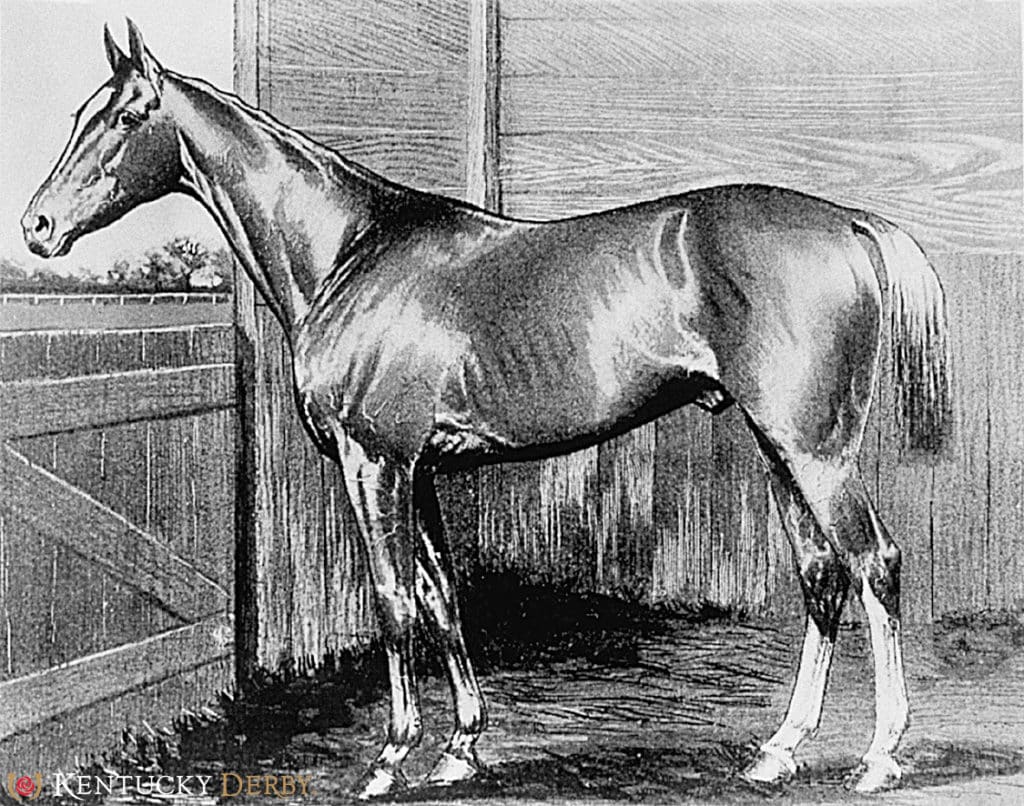

Spokane wins the 1889 Kentucky Derby<br />(Courtesy of the Kentucky Derby/Churchill Downs)

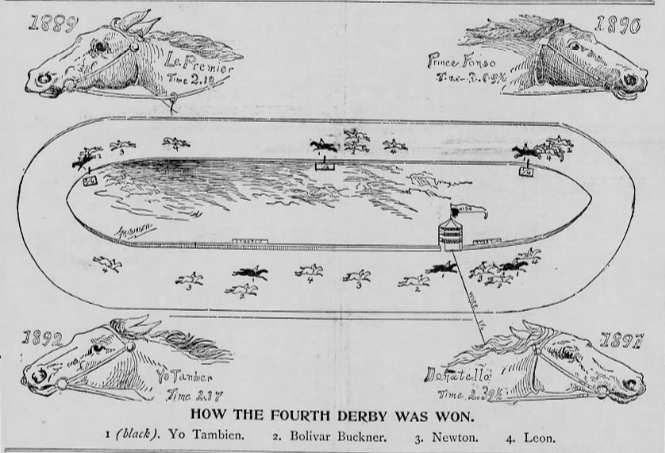

The Twin City Jockey Club stakes program, revealed the previous winter, had as its centerpiece the $2,500-added Twin City Derby for three-year-olds over 1 1/4 miles on the opening day. The Derby would continue to be the Club's annual opening day attraction until its demise.

The Twin City Jockey Club stakes program, revealed the previous winter, had as its centerpiece the $2,500-added Twin City Derby for three-year-olds over 1 1/4 miles on the opening day. The Derby would continue to be the Club's annual opening day attraction until its demise.

Throughout the spring and early summer, the leading candidate being recruited by Shaw for the Twin City Derby was Spokane, a Montana-bred colt who had posted an upset in the Kentucky Derby in track record time and later captured the Clark Stakes (also at Churchill Downs) and the famed American Derby at Washington Park.

On the evening of the American Derby, June 22, Shaw wired the St. Paul Daily Globe:

"Noah Armstrong, owner of Spokane, assures me tonight that nothing but death will prevent the Montana wonder from running at St. Paul. As Spokane is at present fit to run for a man's life, Northwestern turfmen can bet with safety that he will be in the race for the Twin City Derby stakes."

Even though he suffered an interim defeat in the Sheridan Stakes at Washington Park to Proctor Knott, whom he had beaten in the Kentucky and American derbies, Spokane was seemingly still on target to make the long trek north to give Minnesotans a fabulous first taste of the Thoroughbred sport.

Unfortunately, on Derby morning, newspapers reported that Spokane had not arrived on the train from Chicago the previous day as scheduled. Armstrong had wired Shaw in advance that Spokane would be staying home due to illness, presumably an attack of colic.

Unfortunately, on Derby morning, newspapers reported that Spokane had not arrived on the train from Chicago the previous day as scheduled. Armstrong had wired Shaw in advance that Spokane would be staying home due to illness, presumably an attack of colic.

"Col. Shaw was for once in his life thoroughly mad, and his anger was by no means assumed," wrote the columnist 'Truthful James' in the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune. "It was the genuine dyed-in-the-collar, turn-the-hose-on-me brand of madness, and had the colonel at that moment pulled a gun on himself it would have been a case of justifiable homicide, provided the gun was loaded."

Despite attracting only a field of four runners for the feature, the Twin City Derby program was attended by a crowd estimated between 25,000 and 30,000, including the high society of Minnesota politics and industry. The Derby itself was won courageously by Le Premier, who had previously notched the Kansas City Derby and came out of the Twin City Derby lame. The winner's share of $5,000 slightly exceeded Spokane's Kentucky Derby winning share of $4,880.

In a bit of irony, the second race on that opening day card, a selling race at seven furlongs, was won by Cora Fisher, a half-sister to Spokane.

The morning after the first Twin City Derby, the Minneapolis Tribune editorialized on the success of that program and the sport in general. There is much fans of racing would agree with today, nearly 130 years after it was written.

Attendance was not so high the remainder of the meet, especially on Twin City Oaks Day when a mere 3,000 were estimated to have braved soaking weather. However, crowds varied from 5,000 to 8,000 on other days.

The co-leading rider at the inaugural Twin City Jockey Club meet with nine victories was Fred Taral, who later became the regular rider for the legendary Domino and also rode Manuel to victory in the 1899 Kentucky Derby. Taral was among the original inductees into the Racing Hall of Fame when it was established in 1955. (Coincidentally, the leading rider at Canterbury's inaugural season in 1985 was also a future Hall of Fame inductee: Mike Smith).

Another early member of the Twin City Jockey Club riding colony was Tod Sloan, a colorful personality on and off the track who revolutionized race riding when he moved his tack to Europe in the late 1890s. He, too, was an original Hall of Fame inductee in 1955.

Manuel 1899 Kentucky Derby Winner<br />(Courtesy of Kentucky Derby/Churchill Downs)

- 1891: Hamline

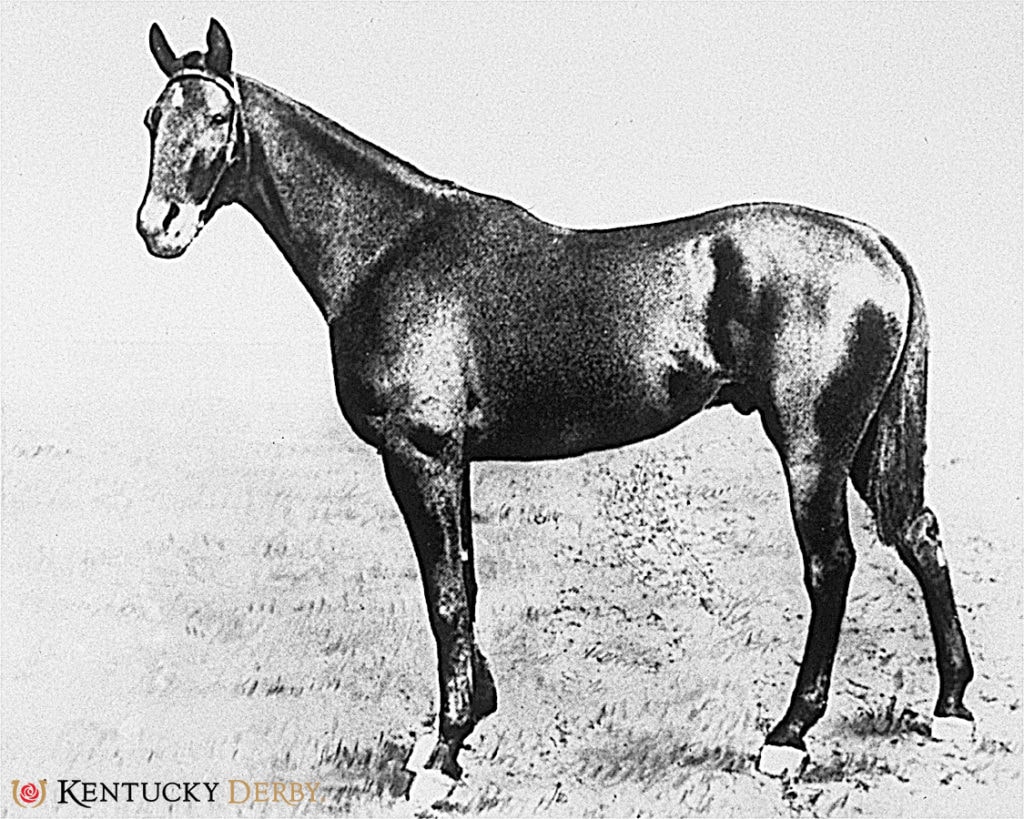

Macbeth II 1888 Kentucky Derby Winner<br />(Courtesy of Kentucky Derby/Churchill Downs)

Located near Hamline University in St. Paul, the fairgrounds track would generally be referred to in the press as "Hamline" or the Jockey Club meet as the "Hamline Races."

Though Spokane failed to show up at Hamline, it wouldn't take until Unbridled in 1989 for Minnesotans to get a look at a past or future Kentucky Derby winner.

Macbeth II, the 1888 Kentucky Derby winner, made two of his 35 starts of the 1890 season at Hamline, which conducted a 10-day meet from July 23 through August 2. None counted among Macbeth II's 10 wins that year as he finished fourth on July 24 and second two days later.

The only horse to have won the Kentucky Derby and raced in Minnesota the same year was Kingman in 1891. Third over 1 3/16 miles on July 27, he rebounded two days later defeating two rivals in a 1 1/16-mile free handicap.

Another horse who found fame in Kentucky in 1891 repeated in Minnesota that year. That was Miss Hawkins, who captured the Kentucky Oaks in the spring and the Twin City Oaks on July 28.

Perhaps the saltiest two-year-old stakes ever run in the "Land of 10,000 Lakes" occurred on July 23, 1891. The 5 1/2-furlong Minneapolis Stakes was won by Carlsbad, who went on to capture the following season's American Derby. Finishing second was a filly named Yo Tambien.

Kingman 1891 Kentucky Derby winner<br />(Courtesy of Kentucky Derby/Churchill Downs)

- 1892: Yo Tambien "Queen of the Turf"

Arguably the most celebrated horse ever to have run at Hamline, Yo Tambien was hailed by the national press as "Queen of the Turf" in 1892 when she won 14 of 16 starts. She was never more dominant than at Hamline, where she won five times during the 23-day meet that ran from July 26 through August 20.

Bankrolling $8,770 for her efforts that summer in St. Paul, Yo Tambien swept nearly every stakes for which she was eligible to run in. After winning the Twin City Derby, she won the 1 3/8-mile Hamline Stakes, in which the bookmakers accepted no wagers on her (though there were some reports of 1-50 odds being available). Yo Tambien then captured the Twin City Oaks over 1 1/8 miles and finally the Twin City Exposition Stakes against older males going 1 1/16 miles.

...the bookmakers accepted no wagers on her...

Such was the legacy of Yo Tambien in Chicago racing circles that beginning in 1953, and for more than four decades afterward, Hawthorne ran the Yo Tambien Handicap in her honor.

Charley Thorpe rode Yo Tambien exclusively at Hamline and won 25 races total during the 23-day stand, an amazing statistic when you consider the typical race card consisted of only five races. Like Tod Sloan, Thorpe later found success in Europe. He was the winning rider aboard Ex Voto in the 1903 French Derby at Chantilly.

Another highlight of the 1892 meet was the victory by Lookout in the 5 1/2-furlong Minneapolis Stakes for two-year-olds. The Kentucky-bred colt won the Kentucky Derby the following spring.

PART II

According to Shaw, the Twin City Jockey Club incurred total losses of $45,000 during its first three seasons, much of it attributed to advertising and the subsidizing of shipping horses from Chicago.

However, the amount lost had declined each year, and there was still a willingness by the Club to invest further, especially after it entered into a 20-year lease with the state fair association to have use of the grounds for a fixed time each year.

A new grandstand was erected at Hamline in advance of the 1892 season. Costing $75,000, news reports noted that it was:

"...nearly 400 feet in length and 60 feet deep, with a seating capacity of between 8,000 and 10,000. The stand is constructed of heavy girders and joists, supported by numerous iron columns, and at once impresses one of its security and durability. The interior is finished in rich Georgia pine, the exterior being painted a delicate slate color."

In addition, the new stand featured box seats on the upper and lower stories, a 50-foot high cupola in the center of the stand for spectators, a betting ring west of the grandstand with 35 bookmakers' blocks, and a paddock beyond that.

As the meetings at St. Paul got progressively longer and encroached on dates of rival tracks, in particular those in Chicago, the opposition began to strike back.

To coincide with the World's Columbian Exposition (or World's Fair) in Chicago, tracks in that city, specifically Washington Park, advertised exorbitant purses for the summer of 1893, an enticement Shaw knew the Twin City Jockey Club could not match.

...After scouting trips to Chicago during the winter...

After scouting trips to Chicago during the winter revealed he would not be able to attract enough horses or patronage without sacrificing the quality of the product, Shaw waved the white flag and announced there would be no summer meet at Hamline in 1893.

Still in the bookmaking business, Shaw was also personally stretched thin financially. According to newspaper accounts, he had paid $100,000 for betting privileges for a 48-day meet at St. Louis and nearly $250,000 for betting privileges for a 25-day meeting at Washington Park that season.

- 1894: The Most Noteworthy Horse

Overlapping dates with Washington Park in 1894 proved unavoidable, so Shaw announced early in the year that racing would return to Hamline that summer with its longest meet ever. Originally scheduled for 30 days, the meet was eventually extended to 43 days, running from June 27 through August 15.

Arguably the most noteworthy horse to have made an appearance at that meet was a rare East Coast invader, Dr. Rice, who had captured the Withers Stakes and placed second in the Belmont Stakes in 1893. Prior to arriving in St. Paul, Dr. Rice had handed future Hall of Famer Henry of Navarre a defeat in the Brooklyn Handicap in New York.

...the St. Paul Daily Globe would eventually describe the race as a "dump,"...

A crowd estimated at 10,000 showed up on Independence Day to watch Dr. Rice compete in the opening event over six furlongs. An anonymous reporter for the St. Paul Daily Globe would eventually describe the race as a "dump," as Dr. Rice finished fourth at odds of 1-6 and that another horse in the race received a "queer ride."

Owner Fred Foster, who had backed Dr. Rice for $3,000 with the bookmakers, immediately canceled his jockey's contract after the loss, but suspicions lingered that there might have been something more nefarious going on.

The following week, the Chicago Tribune would report:

- 1895: Helter-Skelter

William H. P. Robertson, in his 1964 book The History of Thoroughbred Racing in America, wrote:

"In the latter part of the nineteenth century the sport had grown so rapidly and in such helter-skelter fashion that it got out of hand. Race tracks were popping up like dandelions all over the country, and many of them tried to milk a good thing beyond all reason...

"...the 1897 edition of Goodwin's Official Turf Guide had listed 314 tracks running that year in the United States...

"Unfortunately public indignation did not discriminate between the good tracks and the bad, and in the sweeping reforms which followed, the innocent were washed away with the guilty."

Whether the Twin City Jockey Club could be considered among the former rather than the latter is open to debate. Days after the conclusion of the 1894 meet, the St. Paul Daily Globe published this report on page one:

Already having to deal with new anti-poolroom ordinances passed in both Minneapolis and St. Paul, reports of this sort suggested Thoroughbred racing's days in Minnesota were quickly coming to an end.

Citizen petitions and county convention resolutions requesting the prohibition of pool selling and gambling on the grounds of the State Fair, and that the contract between the fair association and the Twin City Jockey Club be annulled, soon reached the state legislature. By spring 1895, the legislature passed a law that did just that and with the governor's approval.

When asked his reaction to the new act, Frank Shaw told the St. Paul Daily Globe:

"I have this to say and no more. The Twin City Jockey Club is the deadest thing that ever lived. There you have it in a nutshell. I repeat it. The Twin City Jockey Club is the deadest thing that ever lived. That is all."

Thus ended the first experiment with Thoroughbred racing in Minnesota, 90 years before the second.

Sources and illustrations:

Chicago Tribune

The History of Thoroughbred Racing in America by William H. P. Robertson

Minneapolis Star Tribune

Minneapolis Tribune and Sunday Tribune

Pacific Rural Press

St. Paul Daily Globe

Thoroughbred Record/Live Stock Record

Site of the Twin City Jockey Club today (Google Maps)

Authors

Categories

Featured Keeneland Products

Kentucky Handicapper's Sheet (PDF)

No one follows the racing in Kentucky better than our handicappers. Get expert selections, in-depth analysis, and wagering strategy daily.

Buy NowSuper Screener

HRN's premiere analysis product, providing selections, analysis & wagering strategy for top stakes every weekend. Mike Shutty uses historical data to screen each race, identifying criteria that helps pick winners & toss vulnerable favorites.

Buy NowBruno With the Works

Bruno De Julio & team bring 30+ yrs experience observing racehorses to Brisnet with valuable insight into their morning routines & chances for success in the afternoons.

Buy NowADVERTISEMENT