A salute to 1943 Triple Crown legend Count Fleet

)

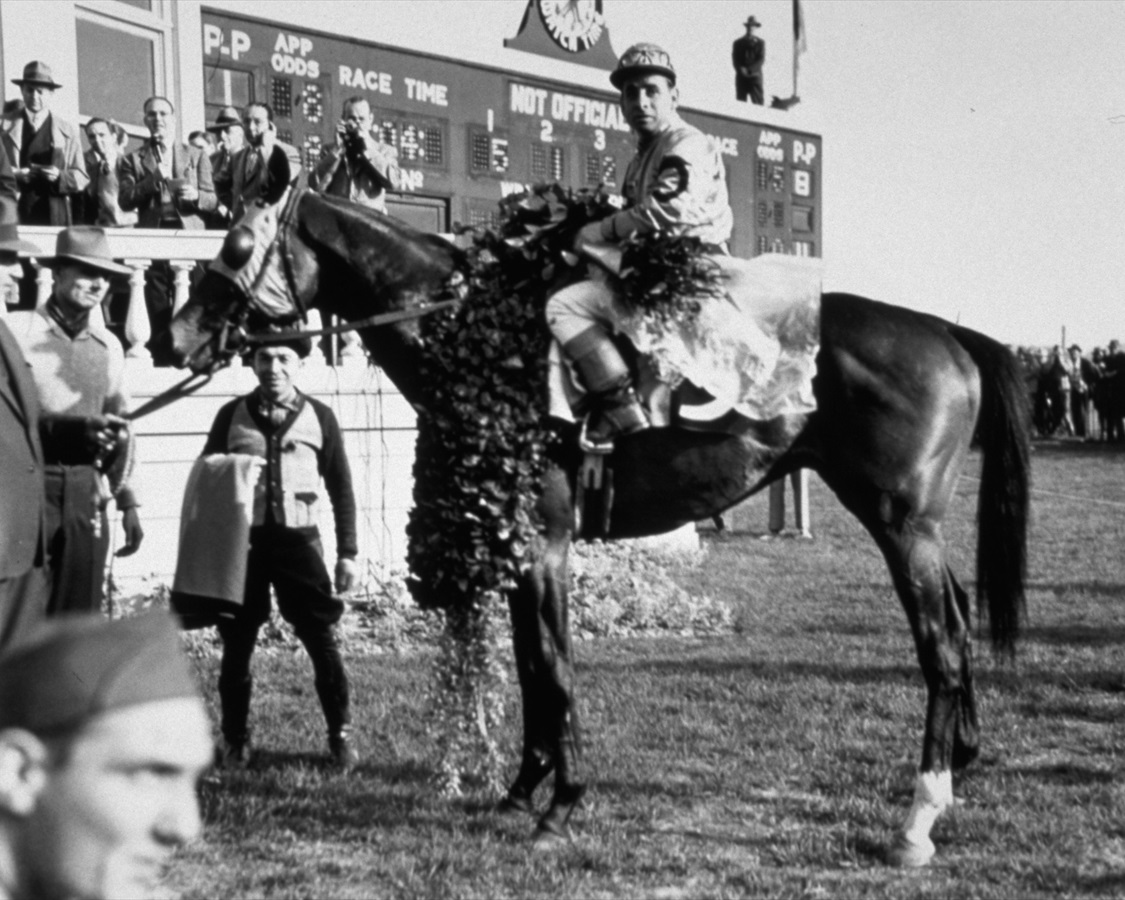

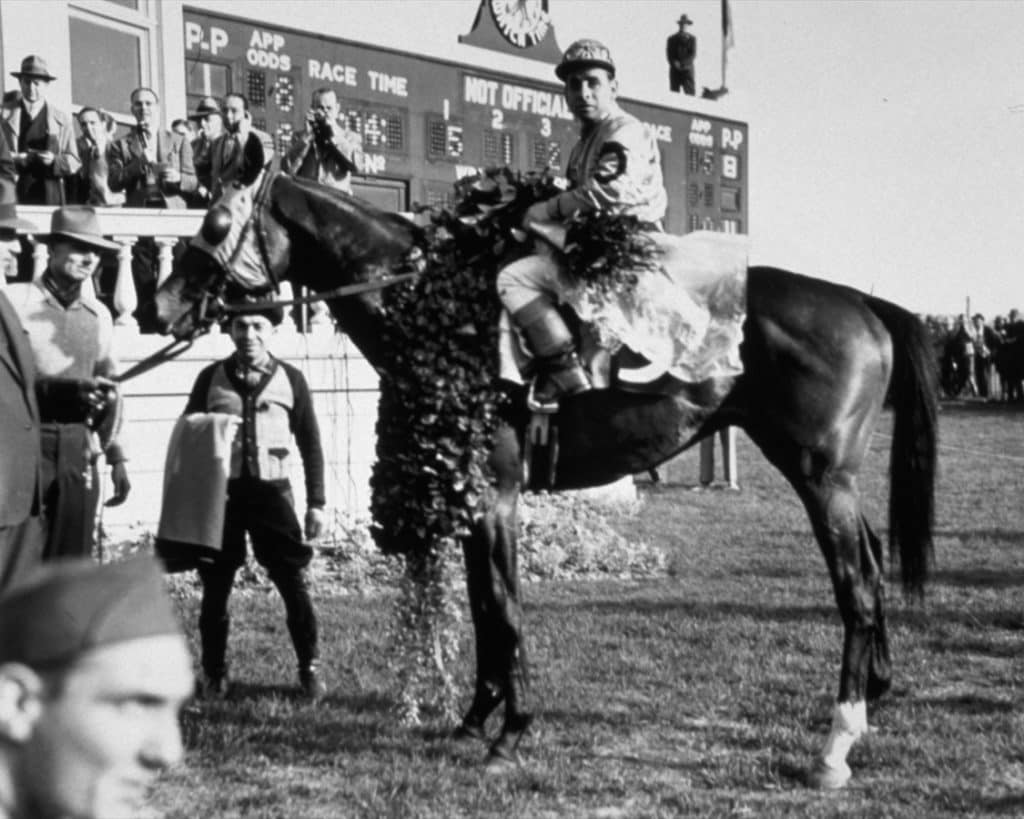

Count Fleet dominated the 1943 Triple Crown but never raced again (c) Churchill Downs/Kentucky Derby Museum

At this time a year ago, as Justify was on the verge of an historic Triple Crown sweep in the Belmont (G1), it did not occur to me that would be the last time we saw the equine meteor in action. An ankle issue surfaced in July, prompting his retirement to stud. His entire racing career spanned fewer than four months.

Although Justify is unique in the record book as a Triple Crown winner who did not race at two, he is the second one to make the Belmont his last hurrah. The first was Count Fleet (1943), thanks to an injury sustained during his 25-length rout in the “Test of the Champion.”

To commemorate Count Fleet, we’re dusting off his story that was originally published in 2008 as one of the "On the Muscle" features on kentuckyderby.com.

****

Imagine a year without the Kentucky Derby. Far from being the premise of a bleak futuristic novel, or a flight of sci-fi fantasy in an alternate universe, it nearly happened in 1943. Confronted by the crushing demands that World War II placed upon both transportation and vital materials, federal authorities suggested that the historic "Run for the Roses" be scrapped that year. Were it not for the shrewd energies of Col. Matt Winn, the legendary Churchill Downs supremo who responded swiftly to meet the government's concerns, Derby lore would have been deprived of one of its greatest champions, Count Fleet.

Count Fleet was a fine proof of the axiom that appearances can be deceiving. Concealed within his smallish, unprepossessing frame was speed of the highest order, matched by boundless stamina and an eccentric willfulness that gave his handlers fits in his younger days. If this member of the equine nobility had a coat of arms, it would be emblazoned with the motto, "Full steam ahead."

The brown colt's odyssey begins with his sire, 1928 Kentucky Derby hero Reigh Count, who caught the attention of John Hertz at Saratoga the summer before his classic success. Hertz, the entrepreneur of Yellow Cab Company and Hertz Rent-a-Car fame, marveled at Reigh Count's fiercely competitive spirit on display in a maiden contest. Storming from far off the pace, Reigh Count drew alongside the leader at the sixteenth-pole, leaned over and sank his teeth into his rival, before surging to victory. Hertz decided then and there to purchase Reigh Count privately.

Reigh Count would reward Hertz's insight into his character. Sporting the yellow silks of Mrs. Fannie Hertz, in whose name all the Hertz horses were campaigned, the chestnut went on to become Horse of the Year in 1928. Reigh Count shipped to England in 1929 and performed with distinction, garnering the prestigious Coronation Cup at Epsom. At stud, he transmitted great staying capacity, but his progeny tended to be later-developing types who lacked speed. Even when Reigh Count's statistics as a sire began to decline, Hertz kept the faith and continued to send a few mares to him each season.

One of those mares was a black speedball named Quickly, who won 32 of 85 starts while competing in much less exalted company than Reigh Count had. Enamored of her pedigree, Hertz bought the daughter of Haste, believing that she would supply the early dash that Reigh Count lacked. His forecast was prophetic, but much time would elapse before the fulfillment.

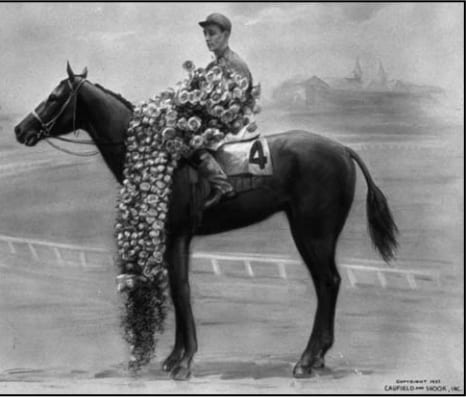

Count Fleet's sire, 1928 Kentucky Derby winner Reigh Count (Courtesy KentuckyDerby.com)

Quickly visited the court of Reigh Count in 1939, several months before the German invasion of Poland ignited World War II in Europe. The following spring, on March 24, 1940, Count Fleet was foaled at Stoner Creek Stud near Paris, Kentucky, but his entrance into the world was far from impressive. The colt was small and sparely made, and his austere looks did not improve as he progressed from weanling to yearling in 1941. Indeed, Hertz put him up for sale that year. The price tag on Count Fleet was set at $4,500, but although a number of horsemen looked him over, there were no takers, and he remained in the Hertz fold.

As war raged halfway round the globe, with the Nazi blitzkrieg penetrating deep into the Russian heartland, Count Fleet began his eventful education. The exuberant colt was difficult to control, and his antics, though not intended to be harmful, were at times downright dangerous for the people around him. Still, in the midst of Count Fleet's quirks, bucks, lurches and eccentricities, his first exercise rider, stable hand Sam Ransom, sensed a serious talent, which Hertz recalled in his Racing Memoirs:

"Mr. Hertz, don't ever sell that leggy, brown colt," Ransom advised. "He has tried to kill me in every way I know of, not out of meanness, but he sure has brushed me up against every tree and barn on the place that he could. Mr. Hertz, when that leggy, brown colt wants to run, he can just about fly."

Decades later, Ransom recounted a very different version of the tale. According to Ransom, he actually approached Mrs. Hertz with the advice not to sell Count Fleet, and Hertz was none too pleased with his meddling. Indeed, Hertz told him flatly not to volunteer such thoughts again.

Count Fleet was slated to take part in the first trial of the Hertz yearlings in November of 1941, weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor plunged the United States into war. Unfortunately, he was forced to sit on the sidelines with a common malady for youngsters, a bucked shin.

In early 1942, Count Fleet was sent to trainer Don Cameron in New York. In an effort to curb the colt's idiosyncratic behavior, he was fitted with blinkers during his exercise, but it was only a partial help. His regular rider, Hall of Famer John Longden, later recalled that Hertz was again trying to sell Count Fleet, worried that the problem colt could wind up hurting his jockey. This time, it was Longden who issued a ringing endorsement of Count Fleet, persuading Hertz to keep him.

After finishing runner-up in his first two outings, Count Fleet began to learn what was required of him. He broke through with back-to-back victories by a combined nine lengths and was promptly regarded as the best two-year-old in the East. Just when it looked like he was putting it all together, however, Count Fleet threw in the worst effort of his career in the Futurity S. at Belmont Park, winding up a distant third. Longden and Hertz offered a colorful explanation for his non-performance. They believed that he was more interested in hanging around the filly, second-place finisher Askmenow, than he was in racing. Other observers discounted that theory. Just days before the race, Count Fleet had drilled six furlongs in a mind-boggling 1:08 1/5, near world-record time in his day, and may have been feeling the effects of that move.

Whatever torpedoed "The Fleet" in the Futurity, he would never again taste defeat. The Hertz colt first perfected the art of front running next time out in the Champagne S., romping by six lengths in a sensational 1:34 4/5 for the mile at Belmont Park. Not only did he set a new track record, but he also established a new world record for a juvenile at the distance. In rapid succession followed similar demolition jobs in an allowance event at old Jamaica, the Pimlico Futurity and the Walden S., embarrassing his opponents by 30 lengths in the latter despite throwing a shoe.

So completely had The Count annihilated his competition, that he was assigned a staggering 132 pounds on the Experimental Free Handicap. No horse, before or since, has ever been so highly rated in this annual assessment of the two-year-old crop, published since 1933. Needless to say, he also garnered champion two-year-old honors.

Meanwhile, as Count Fleet was sweeping all before him in the late autumn of 1942, the American armed forces were engaged in fierce fighting in the Pacific, a new theater of operations had just commenced in North Africa, and a landing on European soil was envisaged for the following year. The home front was of critical importance for the waging of total war. Accordingly, such critical commodities as gasoline were rationed, and the transportation infrastructure was geared to wartime necessities. Therein lay the federal government's concerns about the 1943 Kentucky Derby. If the typical out-of-town crowd tried to get to Louisville, Kentucky, for the first Saturday in May, it would probably cause all manner of headaches for the war effort.

Against this backdrop, Joseph B. Eastman, director of the Office of Defense Transportation, declared over the winter, "It would be better from a transportation stand-point if the Kentucky Derby were not run this year."

The very suggestion was anathema to the larger-than-life Winn, the Churchill Downs president who had transformed the May classic from a low-profile affair into the show-stopping extravaganza that we know today.

"The Kentucky Derby will be run in 1943, even if there are only two horses in the race, and only a half-dozen people in the stands," he promised.

The impresario was determined to stage the 69th Derby, preserving its unbroken line of renewals since 1875, but in a way that would resolve Eastman's worries at a single stroke. Winn averred that it would be held for locals only, eliminating the need for additional transportation, and out-of-towners who already had tickets would be able to turn them in for a refund.

As Winn would go on to proclaim, "We felt it our obligation to the Thoroughbred racing and breeding industry, and to those red-blooded boys who are fighting so magnificently to preserve American ideals and institutions, to maintain the continuity of the Kentucky Derby."

Hence, with the burden of excess train travel effectively removed, Eastman spared the 1943 Derby. Considering Hertz's automotive background, and his wartime service as a transportation adviser to the government, it would have been the height of irony if his star colt were denied his chance of glory because of transportation issues.

Wartime restrictions affected many other race meetings, and in the process, Count Fleet's sophomore campaign. With the old Tropical Park closing early on January 8 because of gasoline rationing, wintering in Florida was not an option. Instead, Cameron shipped the colt, who was still small but started to fill out, to Oaklawn Park to gear up for his assault on the classics.

Count Fleet returned to New York in the spring, and in a time-honored tradition of racing pundits, the question was raised whether he would pick up where he left off, or add his name to the list of juvenile flashes in the pan. He answered in thundering fashion. After coasting home in an allowance on April 13, he cruised by 3 1/2 lengths four days later in the Wood Memorial, then contested at Jamaica. Despite being throttled down by Longden, The Fleet clocked 1 1/16 miles in 1:43, shattering the stakes record by more than two seconds and nearly eclipsing the track mark. His performance was all the more incredible because he had been slammed by a rival at the start, slicing a gash just above his left hind hoof, and blood was trickling from the wound.

An eerily similar injury had befallen his sire just before the Derby, and only after round-the-clock veterinary efforts did Reigh Count make it to the post in 1928. Count Fleet's Derby hopes, once rescued from the imperatives of war, now hung in the balance again. He shipped to Louisville on April 19, and upon arrival, esteemed Daily Racing Form writer Charles Hatton thought the colt's left hind foot looked "mangled."

The Count needed the latest therapies to treat his gash, ward off such potentially serious complications as infection, and ensure his date with destiny beneath the Twin Spires. Part of the coronary band, and the hoof wall, were pared away; sulfanilamide was applied as a topical treatment; ice, the old tried-and-true remedy, was also invoked; and the area was wrapped with a protective bandage. Through it all, Count Fleet appeared sound while training at Churchill, and Hatton, who reported meticulously on the hoof situation, observed that the wound was looking better as the days passed. The champion's connections spoke of their confidence.

"I feel that if the race is at all truly run, it will not be close," Longden prophesied. "The colt loves to run, and he can run. They say he is not much to look at, but he looks mighty good from where I sit when he falls into that long stride."

The fans agreed, and they pounded Count Fleet into 2-5 favoritism in the "Streetcar Derby," so called because of the most accessible manner of getting to the track in those straitened times. Without the out-of-towners -- notably the celebrities, politicians and paragons of high society -- the clubhouse dining room was less densely occupied, and it was also noted that there were fewer people milling around the infield. Still, the crowd officially numbered 61,700, and conspicuous among them were members of the armed forces. Indeed, some were given tickets by generous out-of-town boxholders, who preferred to support the troops instead of pocketing their refunds.

As the Blood-Horse put it, "The Derby had its color, but it was a new color -- khaki."

The khaki was not only represented at the track. Servicemen were able to listen to the race via radio broadcast beamed to far-flung corners of the globe.

Hopes were high among some spectators that, given Count Fleet's penchant for blazing speed, he could set a new record time. What they did not know, however, was that his hoof injury, though progressing nicely, had still altered his training timetable. As Hertz revealed in his memoirs, Count Fleet had been forced to skip at least one key work in the lead-up to the Derby.

Short on fitness or not, The Fleet set sail that May 1 and never looked back, despite the fact that he raced without his left hind bandage, and in the cut-and-thrust of action, his wound reopened. When the starting gate sprang open in the Derby, the usual skirmishing for position ensued, and passing the stands for the first time, The Fleet was momentarily bottled up in traffic. That was not the place Longden wanted to be, not only for tactical reasons, but because of the Hertz colt's intransigence.

As Longden said, "If he didn't have racing room, he'd go to the outside or just climb over horses. If you were in close quarters with him, you were in trouble."

Longden was able to slip through the blockade, and The Fleet rapidly secured his favored battle station -- the lead. Gold Shower, an old opponent from his rowdy juvenile days, tried to match strides with him through the first half-mile in a testing :46 3/5, but Count Fleet was racing in hand, and a spent Gold Shower beat a retreat. On the far turn, another familiar foe, Blue Swords, who had vainly chased him in the Wood Memorial, tried to take aim on Count Fleet, but the effortlessly moving target simply pulled out of his range. In the stretch, the son of Reigh Count drew off to win by three lengths from the valiant Blue Swords, who was himself six lengths clear of third.

Count Fleet dominated the 1943 Triple Crown but never raced again (c) Churchill Downs/Kentucky Derby Museum

Count Fleet took longer to navigate the 1 1/4-mile trip than his most optimistic admirers had imagined, coming home in a slow 2:04 and prompting Hatton to say that the Streetcar Derby was run in "streetcar time." The Count must have taken umbrage at that, for in his three remaining starts, he set or flirted with stakes-record times.

Just one week later, on May 8, Count Fleet lined up for the 1 3/16-mile Preakness S. and turned in an even more commanding performance. Four lengths in front at the first call, he widened his margin throughout, and Hatton believed that the colt responded to the roar of the Pimlico crowd by surging eight lengths clear at the wire. Among those cheering fans was Ransom, now in the Army and based in Maryland. A thoughtful Mrs. Hertz made it possible for him, his Army pals and his commanding officer to enjoy the race, and a victory celebration to boot.

Poor Blue Swords, whose quaint weaponry was always going to be outgunned by The Fleet, was second once more. He pulled up sore and did not try to take on his conqueror again. In the absence of Blue Swords, the Hertz colt faced only two opponents in the one-mile Withers S. on May 22 and duly strolled by five lengths in the Belmont mud.

When Count Fleet lined up in the June 5 Belmont S., seeking a sweep of the Triple Crown, all that stood between him and racing immortality was 1 1/2 miles. The two hopelessly overmatched victims who went into the gate with him hardly qualified as opposition. All The Fleet had to do was complete his victory lap around the oval to claim the laurels. But he wanted to do so much more. Tearing off at the start, the brown colt raced not against his flesh-and-blood foes, but seemed to be vying with history itself. Count Fleet straightaway steamed ahead by eight lengths, then 20 lengths, galloping in majestic isolation en route to a stakes-record final time of 2:28 1/5. At the wire, he was officially credited with a 25-length triumph. Although some felt that was a stingy approximation, it was still enough to set a record margin of victory in the Belmont, a mark which was eclipsed only by Secretariat's 31-length score in 1973.

Eagle-eyed observers, however, noticed that something was amiss during the race. Some believed that they saw him take a bad step entering the backstretch, while others glimpsed a problem in the final quarter-mile. Longden likewise sensed that all was not well.

"I felt him bobble in the stretch and knew he had hurt himself," the Hall of Famer later said. "I started to pull him up, but he'd have none of it. He just grabbed the bit in that bull-headed way of his and took off again."

The Belmont proved to be a Pyrrhic victory, for Count Fleet had suffered an ankle injury. The mishap was brushed aside at the time as not significant, but it developed into a trickier issue than first thought. He wound up never racing again, retiring with a splendid mark of 16 wins, four seconds and one third from 21 starts, and $250,300 in earnings.

Hatton suggested that The Fleet may have been a casualty of the war. In an effort to conserve gasoline, track maintenance was restricted to the early morning hours, and the surface was not watered or harrowed between races. As a result, Hatton noted that the track was "deep in dust… and of somewhat uneven texture" on Belmont Day.

Unanimously voted Horse of the Year for 1943, Count Fleet returned to Stoner Creek, became a prominent stallion, and lived to the advanced age of 33. One of his top sons, Count Turf, captured the Kentucky Derby in 1951, forming the first three-generation series of Derby heroes. The Fleet's enduring legacy, however, came courtesy of his daughters. The great Kelso, a five- time Horse of the Year, was out of a Count Fleet mare, and another daughter of The Fleet became the granddam of the extraordinary Mr. Prospector, whose sire line has enjoyed great success in the past two decades of the Run for the Roses.

In this indirect way, a faint echo of Count Fleet still sounds at Churchill on the first Saturday in May, in the very race that he almost missed. Neither World War II, nor a wounded hoof, were able to forestall his destined glory.

The last word belongs to Longden. Once the world's winningest jockey, he went on to train 1969 Derby winner Majestic Prince, and remains the only person to score Derby victories as a rider and as a trainer. In Longden's appraisal, Count Fleet was the best horse he had ever laid eyes on:

"I don't honestly think the horse was ever foaled who could beat him."

****

Bibliographical postscript: Sources include The Racing Memoirs of John Hertz as told to Evan Shipman; Down the Stretch: The Story of Colonel Matt J. Winn as told to Frank G. Menke; Daily Racing Form, especially Charles Hatton’s reportage; “A Ransom Fit for a Count,” Deirdre B. Biles’ feature on Sam Ransom in The Blood-Horse, April 23, 1988; Marvin Drager’s Most Glorious Crown; Suzanne Wilding and Anthony Del Balso’s Triple Crown Winners; Pohla Smith’s profile of Count Fleet in Thoroughbred Champions: Top 100 Racehorses of the 20th Century published by The Blood-Horse; and “Majestic Times,” Robert Henwood’s feature on John Longden in The Blood-Horse, February 25, 1989.

Video courtesy of Carly Kaiser's YouTube channel

Authors

Categories

FEATURED PRODUCTS

Daily Selections

Full racecard analysis/expert picks for major tracks from America's top handicappers.

Buy Nowe-ponies Picks

E-Ponies computer-based figures have been around since 1997. Using an algorithm written by the business owner and handicapper, Liam Durbin, and powered by BRIS data files, E-Ponies offers a unique, fact-based, dispassionate analysis of every horse in every race, assigning scores for speed, class, form, connections, and more. Forget which jockey owes you money! What does the data say!

Buy NowBruno With the Works

Bruno De Julio & team bring 30+ yrs experience observing racehorses to Brisnet with valuable insight into their morning routines & chances for success in the afternoons.

Buy NowValue Plays AI by Predicteform

Full race card program with easy-to-use win chances and contender classifications for every runner plus analysis of the Best Bet, Live Longshot, and Wagering Suggestions for every race.

Buy NowADVERTISEMENT