Lecomte: The short life but long legacy of a Louisiana racing hero

)

Lecomte portrait from Fair Grounds Racing Museum (Via Bob Roesler's Fair Grounds: Big Shots and Long Shots)

The only horse to beat the legendary racing icon Lexington

About a 10 min. read. For today’s racing fans, the name Lecomte signifies the first of the Fair Grounds scoring races offering points toward the Kentucky Derby (G1). For fans of racing yesteryear, however, Saturday’s 75th renewal spurs thoughts of its 19th century namesake, the horse who handed the legendary Lexington his only loss.

Lecomte and Lexington staged their epic clashes in a different world, not only socially and politically in the antebellum South, but in the manner of racing itself.

They were gladiators of the old system of competing in heats, typically at marathon distances, to determine the race winner. Competitors got only brief respites just to catch their breath between four-mile slogs on the same afternoon.

The Kentucky Derby had not yet been invented, nor had Fair Grounds commenced its official history as a racetrack, when Lexington and Lecomte grappled in the 1850s at New Orleans’ old Metairie Racecourse.

Who was Lecomte?

The archrivals were both sons of the all-time great campaigner Boston, but Lecomte had roots in the Pelican State. He was bred by “General” Thomas Jefferson Wells of the sprawling Wellswood Plantation and its affiliated Dentley property, both south of Alexandria, Louisiana. (This is the general region described by Solomon Northup in his memoir Twelve Years a Slave.)

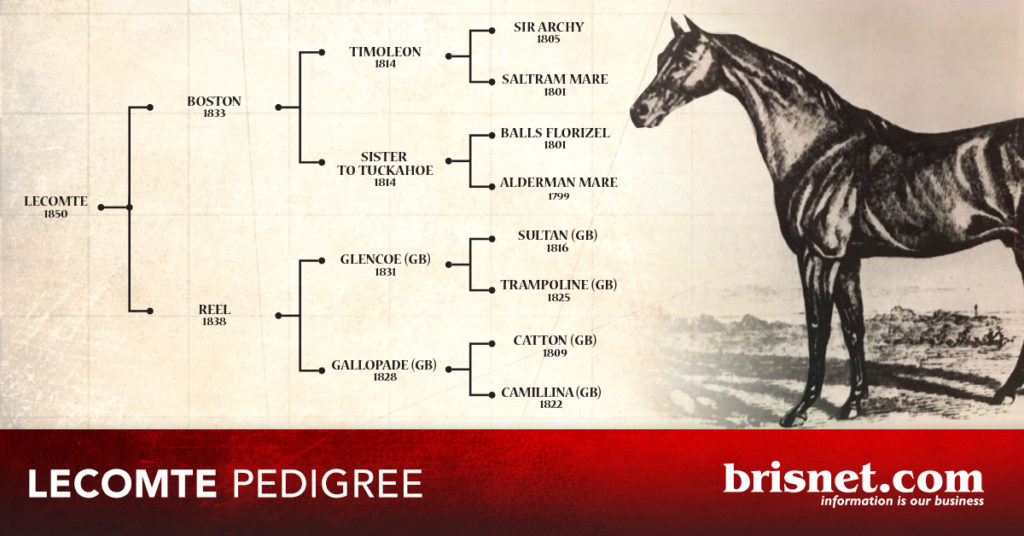

Wells, who studied at Transylvania in Lexington, Kentucky, had an interest in bloodstock. He astutely purchased Lecomte’s dam, Reel, before her racing career. She boasted top British bloodlines as the daughter of two celebrated imports. Her sire, *Glencoe, captured the 2000 Guineas in 1834, added the 1835 Gold Cup at Royal Ascot, and became a phenomenon at stud. Her dam, *Gallopade, defeated males in the 1832 Doncaster Cup and founded a still-illustrious family.

Reel inherited her gray coat from Gallopade, along with the twofold accomplishment of being a high-class racemare and excellent producer. Unbeaten through her first seven races, including a match at Metairie, Reel lost her perfect mark when sustaining a career-ending injury. She transmitted her ability to her offspring. Aside from Lecomte, Reel produced such major winners as Prioress and Starke. Prioress, the namesake of the Saratoga sprint for three-year-old fillies, became the first American raider to plunder a British prize in the 1857 Cesarewitch.

Castrated or shot

Lecomte was Reel’s lone foal sired by Boston, who was in declining health in 1849, the year of their tryst, and succumbed the following January. A charter member of the Hall of Fame, Boston was part of the inaugural class enshrined in 1955. He hailed from the then-dominant sire line of *Diomed, the first Epsom Derby hero and later a British expat in Virginia, where he put his stamp on the nascent American Thoroughbred.

According to lore, Boston was traded to pay off his owner’s card-playing debt, and accordingly was named for the card game. The youngster was so savage in his early training that an adviser suggested he be “either castrated or shot, preferably the latter.”

...his racing career continued, in between stints at stud...

Thankfully cooler, and more patient, heads prevailed, and Boston – along with his reproductive capacity – survived to alter the course of racing history. “Old Whitenose” became a star of the 1830s, and his racing career continued, in between stints at stud, into the early 1840s. Although he won 40 of 45 starts, Boston is best remembered for the match he lost, as a nine-year-old, to the mare Fashion in 1842.

The Natchitoches connection

Lecomte is often described as a Louisiana-bred, but he was foaled at his dam’s residence in Kentucky. He became a Louisianian once dispatched to Dentley as a yearling. There, on the farm renowned for its cold springs, and a training track demarcated by crepe myrtles, the Boston-Reel colt learned his lessons.

Wells decided to christen the chestnut after his friend Ambrose (or Ambroise) Lecomte, a plantation owner in the Cane River area around Natchitoches.

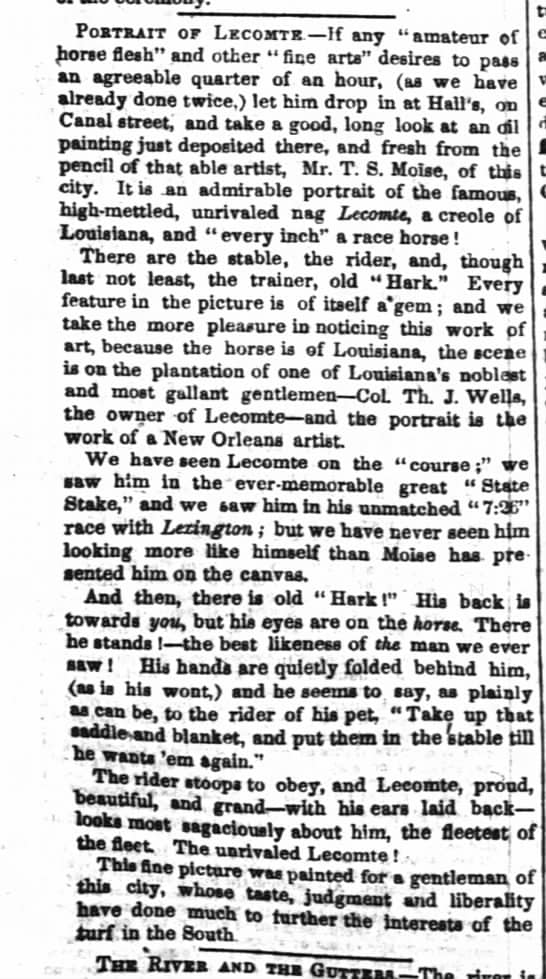

The equine Lecomte was the subject of a word-portrait in the November 9, 1856, Spirit of the Times:

“Lecomte is a rich chestnut, with white on one hind leg, which reaches a little above the pastern joint. He stands fifteen hands, three inches in height. Is in a fine racing form, and well spread throughout his frame, with such an abundance of bone, tendon and muscle, that he would be a useful horse for any purpose. His temper is excellent; he is easily placed in a race, and yet responds promptly to the extent of his ability. He never tears himself and his jockey to pieces by attempting to run away. His action is low, smooth, and easy. His stride is about twenty-three feet, and he gets away from the score like a quarter-horse. He has a constitution of iron, the appetite of a lion, would eat sixteen quarts of feed if it was given to him, and can stand as much work as a team of mules. In a word, he has all the good points and qualities of both sire and dam, without their defects; consequently he is about as fine a specimen of a Thoroughbred as can be found in this or any other country.”

Lecomte opened his career with a five-race winning streak. Because Southern-based horses celebrated their official birthdays on May 1 (instead of the eventual January 1 standard), he was still technically two when capturing his debut in a pair of mile heats in April 1853. Lecomte wasn’t seen again until November at Natchez, Mississippi, where he stretched out to land a sweepstakes in two-mile heats at the classically named Pharsalia Racecourse. During a busy January campaign in 1854, he swept three straight, within a 13-day span, at Metairie.

Then at its zenith, the famed Metairie circuit was to host a prize whose entry conditions faintly echo our modern day Pegasus World Cup Invitational (G1). Only instead of individuals buying spots purely for themselves, the 1854 “Great State Post Stake” would pit representatives of the states against each other. Designated parties would select one horse to fly their state’s flag, for a pricey $5,000 entry fee, in four-mile heats.

This presented a twist on the North-South match-ups that had become a feature of the racing landscape. Regional rivalry was expressed on the track, just as sectionalism was rising in politics in the decades leading up to the Civil War. The Boston-Fashion epic is a case in point, with New Jersey-bred Fashion giving bragging rights to the North.

<em>Life on the Metairie, by Victor Pierson and Theodore S. Moise (Wikimedia Commons)</em>

Lexington's Great State Post

As it turned out, however, only four states competed in the Great State Post, none from the North. Three hailed from the Deep South, while the border Commonwealth of Kentucky furnished Lexington, whose name was changed, after private purchase, to highlight his affiliation.

The native New Yorker made the venture more alluring...by renaming the colt in honor of his hometown.

In fact, Lexington was specifically bought by Richard Ten Broeck, then the majority shareholder in the Metairie course, as a recruit for – and a way to boost – the Great State Post. The native New Yorker made the venture more alluring to his new Kentucky partners by renaming the colt in honor of his hometown.

Lexington, like Lecomte, brought a perfect record into the Great State Post. (He dropped a heat once, but that did not count as a loss since he roared back in the next heats and won that race overall.) Originally named Darley, owing to his resemblance to the iconic portrait of the Darley Arabian, he retained the winning habit once moving to Metairie for his new connections.

Reminiscent of the Pegasus, some shuffling was involved to align the slots with the interested parties. Lecomte ended up representing Mississippi, with Arrow gaining the Louisiana spot, and Highlander was the hope of Alabama.

Betting the Farm

As a measure of the race’s significance, Millard Fillmore, a year removed from the White House, served as one of the official judges. Steamboats were chartered for Kentucky fans to make the journey from Louisville to cheer on Lexington, while local hero Lecomte had his partisans literally in the house.

Two of them were a young B. Frank Moore and his father. A half-century later, Moore recalled a chance meeting at the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans. His father bumped into W.J. Minor, who was hosting Lecomte in advance of the race. There had been whispers of a superb final workout…could Minor comment?

Minor said he’d literally bet the farm on Lecomte if it were a fast track: “everything on earth I possess would go on that horse beating any horse in the world that could be pitted against him.” But muddy conditions favored Lexington:

“The track, however, is very heavy and stiff in mud, and Lexington coming down here as a noted mud horse, I would not risk one cent on Lecomte.”

That judgment proved spot-on, for Lexington rolled on the off track to hand Lecomte, runner-up in both heats of the Great State Post, his first defeat. As a measure of just how heavy the track was, Lexington needed 8:08 3/4 to negotiate the four miles of the first heat and 8:04 to clinch the victory in the second.

One Week Later...

But one week later in the Jockey Club Purse, the track was fast, and Lecomte turned the tables. Lexington fans point out that one of his co-owners wanted to give him time off after his dominant performance in the Great State Post, and had already hung up his horseshoes, only to be overruled by Ten Broeck. A reshod Lexington was pitched back into the lists.

In any event, Lecomte delivered an effort for the ages, in record time. Aside from the conditions that suited him, Lecomte also got a key rider change to Abe Hawkins.

...his aerodynamic riding style would influence future generations of jockeys, including Tod Sloan.

Described as the first African-American to be acclaimed in the sports world, Hawkins was still subject to the institution of slavery, and he’d been bought as human chattel. Hawkins would go on to success after the Civil War as well, most notably winning the 1866 Travers, and his aerodynamic riding style would influence future generations of jockeys, including Tod Sloan.

Lecomte’s trainer was a slave himself, known simply as “Hark,” underscoring the oft-forgotten role played by African American horsemen of that era. Hark was adamant that “Abe” would lift Lecomte in the rematch with Lexington. If his mount had the requisite combination of speed and stamina, Hawkins doled it out with measured perfection.

As the New Orleans Picayune recapped, Lecomte set the pace in the first four-mile heat. When Lexington tried to take runs at him, “the attempt was immense and elicited the loudest encomiums from Lexington’s friends and backers, but it was ineffectual.”

Repelling his archrival’s every bid, Lecomte drew off by six lengths. And the margin wasn’t even the biggest shock.

“If the result of the heat induced great shouting, the announcement of the time produced still more clamorous demonstrations of delight. All knew that the heat was fast, but each one of the hundred persons who held watches could scarcely believe their own time until the judges announced it officially.”

The time was 7:26 flat – obliterating the old four-mile record of 7:32 1/2 set by Fashion in her victory over Boston. You might say that Boston got posthumous satisfaction.

Although Lexington appeared more wrung out by the experience than the fresh Lecomte, he revived well for the second heat and took command through the first two miles. Then Lecomte made his move:

“Both now did their best, and the third mile was a constant strife throughout, for the lead, and the quickest in the race, being run in 1:46; but Lecomte, although so hard pushed, never wavered, but ran evenly and steadily along about two lengths ahead. On the first turn of the fourth mile, Lexington, who at that point was nearly up to his rival, for a moment gave back and lost his stride, but he at once recovered it, and pushed on with vigor, but with evidently great effort. All was of no use…”

Lecomte held sway by four lengths. Although he understandably took longer to complete the second heat, coming off the heels of the record-shattering first, his time of 7:38 4/5 was still faster as a follow-up. Fashion, for instance, regressed to 7:45 to polish off Boston in their second heat.

That left the New Orleans Picayune correspondent giddily hyperbolic:

“well satisfied that we have witnessed the best race, in all respects, that was ever run, and that Lecomte stands proudly before the world, as the best race-horse ever produced on the Turf.”

Back in the neighborhood of Dentley, an outpost was renamed in honor of the hometown celebrity. A painter misspelled it on the railroad depot, so the story goes, and that’s how Lecompte, Louisiana, got on the map.

But Lexington partisans seized upon another excuse. Arguing jockey error was to blame for easing up momentarily going into the last mile, Ten Broeck took to Spirit of the Times to agitate for a third round. He spelled out terms, including the option of Lexington racing versus the clock to beat Lecomte’s record.

The time challenge came off nearly a year later, on April 2, 1855, over the same track. Lexington was assisted by a running start and a relay team to ensure he put forth the maximum effort. As if he’d been stewing over his loss, and determined to reclaim his supremacy, he annihilated the record.

Under 103 pounds, 14 more than Lecomte carried the year prior, Lexington flew in 7:19 3/4. The Metairie crowd erupted at the time because his “deceptive, fox-like gait” had camouflaged his speed.

Now the stage was set for the rubber match with Lecomte. Tourists packed the city, all buzzing about the race, much like talk of the “big game” among football fans:

“All sorts of wagers were laid, all kinds of speculations indulged in. Lexington and Lecomte were the great lions of the day, and bulletins from their respective stables were waited for and read with the same interest and avidity as though they announced possible change in a dynasty or the probable fate of a nation. The race was the talk of the street corners, on ‘change, on the Rialto ‘where merchants most do congregate,’ in the private as well as the public circle, by all sorts and conditions of men, women, and children. In brief, it was the ruling idea of the hour. Nothing could supersede or stand beside it. The race, the whole race, and nothing but the race.”

Unfortunately, the event was a letdown for Lecomte fans. Rumors swirled during the week that he’d had colic. While he presented a lovely appearance going to post, Lecomte was uncharacteristically outpaced early in the first heat.

“In vain Lecomte struggled; in vain he called to mind his former laurels; in vain his rider struck him with the steel; his great spirit was a sharper spur, and when his tail fell, as it did from this time out, I could imagine he felt a sinking of the heart as he saw streaming before him the waving flag of Lexington, now held straight out in race-horse fashion, and anon nervously flung up, as if it were a plume of triumph.”

Wells did not put Lecomte through the misery of a second heat. He was withdrawn on the spot. Wells later fell into insinuations about whether he’d been betrayed, if Lecomte had been “gotten to,” in a sad and messy coda to the loss.

Lexington had the additional satisfaction of lowering the four-mile race record to 7:23 1/2 (in competition as opposed to running against the clock), in what turned out to be his last hurrah. As had happened to Boston, Lexington was losing his eyesight, and retired to a breed-shaping stud career. The “Blind Hero of Woodburn” topped the American sires’ list 14 straight years, 16 in all, and rewrote Thoroughbred pedigrees in the ink of his own blood.

<em>Lexington's skeleton displayed at the Kentucky Horse Park with his portrait by Edward Troye (Kellie Reilly photo)</em>

A Twist...

In a plot twist, Ten Broeck bought his old foe Lecomte and sent him to Great Britain as part of a small but select raiding party, including his aforementioned half-sister Prioress. He was entitled to make a splash, but a series of setbacks had taken their toll. Previously sidelined by foreleg trouble, he reportedly came down with pneumonia on the ship. Lecomte disappointed in his only English start, later fell ill with colic, and died in 1857.

But his story does not have a dead end. While resting his legs prior to export, Lecomte bred a few mares in 1856.

One was the dam of Lexington, Alice Carneal.

One was the dam of Lexington, Alice Carneal. Their son, Umpire, became a smart performer in England. Not disgraced when unplaced as the third choice in the 1860 Derby at Epsom, Umpire scored his biggest win in the 1863 King’s Stand. He fell into obscurity at stud, but not before leaving a trace of Lecomte’s genes in his new homeland. Umpire’s daughter, Wrangle, is the direct female-line ancestress of several major winners. Her descendant Quashed, the 1935 Oaks victress, famously overturned Triple Crown winner Omaha in the 1936 Gold Cup at Royal Ascot, and her more recent representatives include champions Sonic Lady and Attraction.

Lecomte’s most enduring legacy in bloodlines, though, comes via a Wells-bred daughter, and fittingly intertwined with Lexington. Wells bred his unnamed “Lecomte mare” to War Dance, a son of Lexington (and half-brother to Lecomte). The resulting filly, Lizzie G., would go on to become the maternal granddam of the immortal Domino.

While Domino is the chief vector keeping Lecomte’s name in pedigrees, Lizzie G. sports a whole tribe of matrilineal descendants, including influential sire Hamburg, fellow Hall of Famer Twilight Tear, and 1978 Triple Crown legend Affirmed.

Lecomte and Lexington are long gone, and Metairie Racecourse converted into a cemetery the decade after the Civil War, but their echoes can still be heard. Today’s champions, their descendants, breathe the fiery spirit of battles around old Metairie.

Inspired to participate in the running of the Lecomte? Find the race at Fair Grounds on TwinSpires!

Sources consulted

New Orleans Picayune and Spirit of the Times material (unless otherwise noted below) from Henry William Herbert, Frank Forester’s Horse and Horsemanship of the United States, p. 311 (word portrait in Spirit of the Times), pp. 316-18 (Picayune on Lecomte victory); p. 327 (Lexington race against the clock from Picayune); and p. 335 (Lexington victory recapped by Spirit of the Times).

William H.P. Robertson, History of Thoroughbred Racing in America, pp. 68-77.

Kent Hollingsworth, Kentucky Thoroughbred, pp. 22-32

Background on T.J. Wells – Sue Eakin, Rapides Parish History http://www.rapidesgenealogy.org/history/eakin/eakin2.htm

Boston and Reel - Anne Peters’ portraits on Thoroughbred Heritage

http://www.tbheritage.com/Portraits/Boston.html

http://www.tbheritage.com/Portraits/Reel.html

Lecomte Kentucky-born – Jacob Pincus recollection in Daily Racing Form, November 15, 1913

Dentley and the town Lecompte - Alexandria Daily Town Talk, Centennial Edition, March 18, 1983

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7216822/thomas_jefferson_wells

B. Frank Moore’s letter – Daily Racing Form, November 11, 1910

Picayune scene-setter of April 14, 1855 – Daily Racing Form December 20, 1914

Nick Weldon, “From slavery to sports stardom: Abe Hawkins’s rise from a Louisiana plantation to horse-racing fame,” on Historic New Orleans Collection website

Annie Johnson, “Legacy of Triumph: More Stories of Duncan F. Kenner and Abe Hawkins at Ashland Plantation,” on Antebellum Turf Times

Katherine C. Mooney, Race Horse Men

Bob Roesler, Fair Grounds: Big Shots and Long Shots

<em>A Portrait of Lecomte and Trainer Old 'Hark' news clipping from The Times-Picayune</em>

Authors

Categories

FEATURED PRODUCTS

Chalk Buster Pick of the Day

In depth analysis, comments and wagering strategy on the one race which is selected as Pick of The Day!

Buy NowBruno With the Works

Bruno De Julio & team bring 30+ yrs experience observing racehorses to Brisnet with valuable insight into their morning routines & chances for success in the afternoons.

Buy NowDaily Selections

Full racecard analysis/expert picks for major tracks from America's top handicappers.

Buy NowADVERTISEMENT