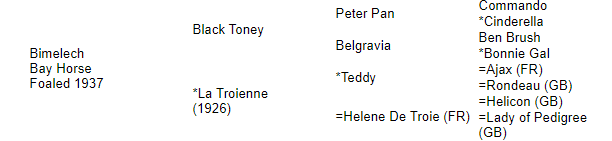

Had Keeneland’s spring meet gone forward, we might have seen unbeaten Maxfield launch his comeback in the Blue Grass (G2). Instead I’m finding refuge in the past, and a perusal of the Blue Grass honor roll led me to back to Hall of Famer Bimelech (1940).

Col. E.R. Bradley’s homebred likewise made his sophomore debut in the Blue Grass, but later lost his perfect record in one of the biggest upsets in Kentucky Derby history. Bimelech went on to take the Preakness and Belmont, and in different circumstances, perhaps should have swept the Triple Crown.

A son of the blue hen *La Troienne, Bimelech was the younger full brother of Hall of Famer Black Helen, who beat males in the 1935 American Derby and Florida Derby. His other full sister was 1938 Selima winner Big Hurry. Both are remembered more now as influential broodmares, with Big Hurry the ancestress of Easy Goer, Sea Hero, Affectionately, and Allez France while Black Helen’s descendants include 1994 Derby upsetter Go For Gin.

Bimelech was the third act of that all-star sibling trio, indeed the last colt from the miniscule final crop sired by Black Toney. Bradley had long desired a colt from the Black Toney-La Troienne marriage, and Bimelech fulfilled those hopes in more ways than one.

This image is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced in print or electronically without written permission of the Keeneland Library.

In keeping with the familiar Bradley pattern, his name was always going to start with the letter “B.” But in his case, it required a bit of finessing because his actual namesake was “Abimelech.” That was the nickname of Bradley’s friend John Harris. According to sports writer Frank Menke, Harris was given the moniker by his uncle, after one of his favorite Biblical personages. (No word on which of the Abimelechs was intended – presumably the one in Genesis.)

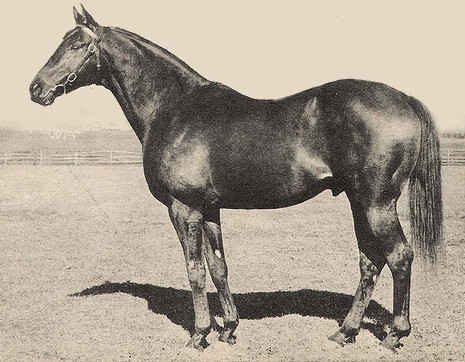

With the passing of Bradley’s top trainer, “Derby Dick” Thompson, Bimelech was developed by Bill Hurley. The bay ranked as an exceptional prospect from the beginning, his bloodlines translating into a fine physique and early signs of ability.

As William H. P. Robertson recounts in his History of Thoroughbred Racing in America, Bradley and Hurley “agreed he was one of the best they had ever seen, regardless of breeding” (p. 333).

Bimelech’s reputation preceded him when he was unveiled at Suffolk Downs June 28, 1939. Dispatched as the 9-5 favorite, he vied through a swift pace, put his foes away, and won by three lengths “easily” as the chart comment indicates.

Next seen in a July 14 allowance at old Empire City, Bimelech performed up to his 3-5 billing. He grabbed the lead and widened his margin to six lengths to elicit the comment “much the best.”

The Daily Racing Form recap (accessible at drf.uky.edu) noted that Bimelech did especially well considering the slow track. The article, fittingly headlined “Black Helen’s brother wins,” further observed that Bimelech was emulating his champion sister’s running style:

“As Bimelech came romping through the stretch to a very easy triumph…memories of his dazzling sister Black Helen were revived in the minds of the more studious followers of horses. Black Helen it was recalled was a filly possessed of extreme speed and the ability to carry it over a distance of ground. It also was recollected that in 1935 she defeated a crack field of both sexes in the Florida Derby – now the Flamingo Stakes – and that later in the year she won among other important engagements the Coaching Club American Oaks.”

Bimelech earned championship honors himself by finishing his juvenile campaign unbeaten. After wiring the Saratoga Special “going away” by three lengths, he was clearly the one to beat in the Spa’s marquee event for 2-year-olds, the Hopeful. Rival jockeys were bent on ganging up to do just that, as Ken McLean recounts in Quest for a Classic Winner (p. 193):

“…a scrimmage occurred during the running of the Hopeful Stakes and jockey Freddy Smith was the victim of a plot by other jockeys to jam Bimelech in on the rails. Fortunately a small opening came for the colt midway down the stretch and Bimelech accelerated to catch Andy K. and win by a neck.”

That description furnishes the color missing from the trouble line “impeded start, stretch.” Aside from gaining credit for overcoming a rough trip, Bimelech showed the rare quality of being able to win despite an enforced change of style. His chief weapon was his early speed, and the chance to use it was denied him here.

This image is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced in print or electronically without written permission of the Keeneland Library.

Bimelech employed that speed to full effect in the Futurity at Belmont, prevailing “in hand.” Stretching out to 1 1/16 miles in the Pimlico Futurity, he stalked in second before driving four lengths clear, again “going away.”

Now a perfect 6-for-6, Bimelech instilled such confidence in Bradley that the sharp gambler tried to lure the older stars into taking on his juvenile. There were no takers, as Robertson explains (p. 334):

“It was then that Bradley issued his challenge to any horse in training, Challedon and/or Kayak II preferred, ‘for money, marbles, or chalk,’ for a race at a mile and 70 yards or 1 1/16 miles at weight for age. Since any older rival would have had to concede Bimelech at least 20 pounds by the scale of weights – and his contemporaries already had seen more than enough of him – no one wanted any part of such a race, so Bimelech went home as the heaviest future book favorite for the Kentucky Derby in history. He was assigned an unprecedented 130 pounds on the Experimental Free Handicap.”

Bimelech wintered at his Kentucky home, Bradley’s Idle Hour Stock Farm, while Hurley was in Florida. But he apparently wasn’t getting fit enough on the farm, and that was a precursor to his shock loss in the Derby. Abram Hewitt paints the picture in his Great Breeders and Their Methods (p. 116):

“When trainer William Hurley came from Florida in the spring of 1940, he found Bimelech fat and backward in his training for the Kentucky Derby. He gave Bimelech a hurried preparation for the Blue Grass Stakes…”

Bimelech flaunted his class despite the lack of fitness in the 1 1/8-mile Blue Grass. The 1-10 favorite dashed to the lead and bested Roman “in hand” at Keeneland. That effort off the six-month holiday on April 25 could have set him up for the Derby just nine days later. But Hurley insisted on running him again in between, contrary to some friendly advice from Hall of Fame horseman Ben Jones. Hewitt recalls Jones saying:

“Bimelech is not really ready, but he can win the Kentucky Derby if he is not raced again before the Derby.”

Persisting to wheel back for the April 30 Derby Trial, Bimelech set fast fractions and held sway in what turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory. Back-to-back runs off the layoff left their mark on what was to have been the biggest race of his life.

Nevertheless, even an off-form Bimelech gave his backers a run for their money in the Derby. The 2-5 favorite took command from fellow speedster Roman turning for home, but instead of pulling away, he uncharacteristically began to tread water.

Sneaking through on the rail came 35-1 longshot Gallahadion, who had been second in the Derby Trial, and now gained improbable revenge. Campaigned by candy tycoon Ethel Mars’ Milky Way Stable, Gallahadion sprang the biggest Derby upset since Donerail’s famous 91-1 in 1913. Not until the turn of millennium was he overtaken by Giacomo (50-1 in 2005), Mine That Bird (50-1 in 2009), and Country House (65-1 in 2019).

Bimelech, who salvaged second by a nose, became the shortest-priced Derby favorite to lose since the 1-3 Lieber Karl missed to Plaudit (1898).

Bradley, a four-time Derby winner, failed to add a fifth with the colt he reportedly regarded as his best. Ironically, the other in contention for Bradley’s all-time top colt, Blue Larkspur, was himself a frustrating Derby fourth in 1929. They came from the same sire line, with Blue Larkspur being by the Black Toney stallion Black Servant, who had his own tale of Derby woe when pipped by second-string stablemate Behave Yourself in 1921. Thus Black Toney, sire of Derby winners Black Gold (1924) and Brokers Tip (1933), arguably deserved to have two more if Black Servant and Bimelech had better luck.

The week between the Derby and Preakness helped Bimelech bounce back. Fans kept enough faith to send him off as the 9-10 favorite at Pimlico, and he duly obliged in front-running fashion by three lengths. Mioland finished second, and Gallahadion was put in his place in third.

Bimelech tried to execute another quick turnaround for the Withers on May 18. More bettors rejoined the bandwagon, only to have the 1-10 favorite sustain another loss. Bimelech never made the lead and ended up second to Corydon.

If that reinforced the suspicion of his delicacy, Bimelech responded to the break leading up to the June 8 Belmont. He prevailed in the 1 1/2-mile Test of the Champion by pouncing on early leader Andy K. and holding the rally of Your Choice by three-quarters of a length. Bimelech had the added satisfaction of seeing Gallahadion and Corydon trudge home the last two across the wire in the six-horse field.

The rest of Bimelech’s career is anticlimactic. McLean relates that he came out of the Belmont with an injury and never should have run in the Arlington Classic, where he wound up a distant third to Sirocco and Gallahadion.

The Blood-Horse’s Silver Anniversary Edition reports (p. 152):

“After the race (the Arlington Classic) it was discovered that he had broken the bar in one foot, and the injury had apparently been troubling him for some time. He was taken out of training until the following winter, and an attempt was made to bring him back in Florida. But he did not race kindly, and after finishing fourth in the Widener Handicap of 1941 – the only time he was unplaced – he was taken out of training.”

Retired with a mark of 15-11-2-1 and earnings of $248,745, Bimelech leaves a series of what-ifs from his sophomore season, although he still earned the champion 3-year-old colt title. And he beat sister Black Helen to the Hall of Fame, as the siblings were enshrined in 1990 and 1991, respectively.

Bimelech continues to factor in pedigrees. His leading earner, Better Self, became a successful broodmare sire. Among Better Self’s daughters were Aspidistra, dam of Hall of Fame half-siblings Dr. Fager (broodmare sire of Fappiano) and Ta Wee; Prayer Bell, who produced champion Silent Screen; and the prolific Lady Be Good, whose descendants include Wavering Monarch (sire of Maria’s Mon). Another son of Bimelech, the otherwise obscure Jabneh, can be found on the dam’s side of Deputy Minister.

Bimelech’s best daughter, Be Faithful, was a major winner on the racetrack and an influential producer. Heroine of the 1947 Hawthorne Gold Cup H., 1946 Vanity H., and consecutive runnings of the Beverly H., Be Faithful produced Lalun, the 1955 Kentucky Oaks and Beldame winner. Lalun has bequeathed an enduring legacy as the dam of Never Bend and Bold Reason. Never Bend is the sire of Mill Reef and Riverman, while Bold Reason sired Fairy Bridge, the dam of Sadler’s Wells and Fairy King.

Be Faithful’s full sister, Bimlette, captured the 1946 Frizette and produced No Robbery. The broodmare sire of Estrapade and Criminal Type, No Robbery also appears in the maternal half of Scat Daddy’s pedigree. Another Bimelech mare, Red Stamp, was the dam of champion Porterhouse, who factors on the dam’s side of Meadowlake and Leo Castelli (in turn the broodmare sire of Indian Charlie).

If Bimelech did his part as *La Troienne’s stand-out son, her daughters have diffused her blood far and wide. One of Bimelech’s half-sisters by Blue Larkspur, Businesslike, gained everlasting fame through daughter Busanda, herself the dam of all-time great Buckpasser. And to bring us full circle, Busanda is also the direct maternal ancestress of Maxfield – another sign of the interconnectedness of our sport.

Lede feature photo depicts Bimelech and jockey Fred A Smith in the 1940 Belmont Stakes winner’s circle. The image is courtesy of the Keeneland Library Cook Collection – This image is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced in print or electronically without written permission of the Keeneland Library.